Staffel and Squadron (Part 1)

Dr Victoria Taylor examines how British and German aviators viewed one another during the First World War - and how such perceptions later carried on into 1939

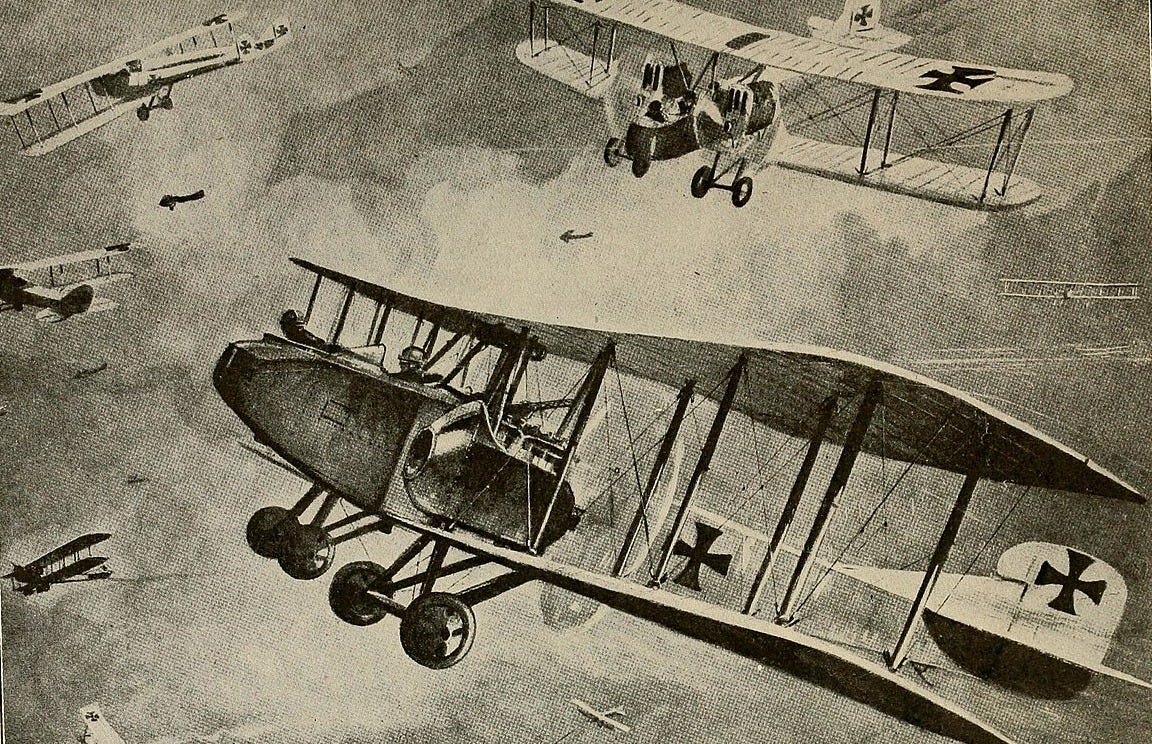

‘Type of Germany’s Long-Distance Bombing Machines’, The people's war book; history, cyclopaedia and chronology of the great world war, 1919 (© Wikimedia Commons)

‘It is a strange spectacle,’ as the German fighter ace Rudolf Stark notes thoughtfully in his diary. ‘A thing that I have been fighting, a thing that was turning its guns on me, a thing I could hardly see at all in the hustle of our turns - and now it stands quite quietly before me.’[i] Stark and his men are cautiously approaching two British airmen whose aircraft have just been brought down by the Germans. ‘The pilot, an English lieutenant, is lifted out of his seat,’ he further details. ‘He has a bullet in the upper part of the thigh. The gunner, a sergeant, is unwounded. Both look very unhappy, but their faces brighten up when they catch sight of me.’

Stark immediately wonders what they are so happy about: after all, ‘it is rather an unpleasant business to fall into the hands of the troops; they are not very kindly disposed towards enemy airmen, especially if they have just had a few bombs dropped on their huts.’ But, as Stark nervously locks eyes with his enemy:

‘The two Englishmen are delighted to see a German airman come along. We greet one another almost like old acquaintances. We bear no malice against one another. We fight each other, but both parties have a chance to win or lose. In a kind of a way we are one big family, even if we scrap with one another and kill one another. We get to know the respective badges of Staffel and Squadron and are pleased to meet these old acquaintances in the flesh. The fight is over, and we are good friends.’[ii]

This intense tale of foes-to-friends sounds as if it could have been a Boulton Paul Defiant crew accidentally downed over Dunkirk, or disorientated amid the Battle of Britain. In reality, it took place during the First World War, when the British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) scrapped ceaselessly with the German Luftstreitkräfte (Imperial German Air Service).

Their dogfights were for King and Kaiser, not King and Führer; they were fought not overwhelmingly with sleek all-metal monocoque fighters, but largely with biplanes and triplanes held together by canvas, wood, hope and a prayer.

What remained consistent across the two World Wars, however, was the general camaraderie between the opposing aviators and the bonding that their common wartime experiences facilitated. A similar attitude was reported by some of the British fighter aces who came up against their German counterparts in the First World War. James McCudden once wrote of how:

‘…the German aviator is disciplined, resolute and brave, and is a foeman worthy of our best. I have had many opportunities of studying his psychology since the war commenced, and although I have seen some cases where a German aviator has on occasion been a coward, yet I have, on the other hand, seen many incidents which have given me food for thought and have caused me to respect the German aviator. The more I fight them, the more I respect them for their fighting qualities. I have on many occasions had German machines at my mercy over our lines, and they have had the choice of landing and being taken prisoners or being shot down. With one exception they chose the latter path.’ [iii]

Thus, in order to comprehend the evolution of Luftwaffe attitudes towards fighting their island foe during the Second World War, it is helpful to firstly recount the formation of their forebearer’s attitudes towards British airmen during the First World War – particularly when many of the young Luftstreitkräfte men who faced Tommy above the trenches would go on to command the Third Reich’s Luftwaffe.

Indeed, the latter’s future Commander-in-Chief, Hermann Göring, had been a famous Luftstreitkräfte fighter ace himself and was the last – albeit unlikely - commander of Manfred von Richthofen’s iconic Jagdgeschwader 1 (‘fighter wing’), better known as the ‘Flying Circus’. Germany’s aviators tended to perceive their experiences in the war far more favourably than other branches of the Imperial German forces.

Unlike their mud-bound brothers in the army, German pilots transcended the meat grinder experience of the trenches. And, unlike their seaborne Kaiserliche Marine (‘Imperial Navy’) counterparts, the aviators had more autonomy over when, where, and how they fought. In his interwar biography of the celebrated Bavarian fighter ace Max Ritter von Müller, Hans Haller explained the unique appeal of combat for the fighter ace:

‘Whilst down below the armies dug deeper into the earth as the trenches solidified into concrete and a belt of machine gun ammunition almost counted for more than the bravery of a warrior, a new war arose, up in the air. There was again man and courage; there was hunting and the landing of blows. This was another fight, the ancient fight – like knights in the tournament they stormed each other, the knights of the World War, the fighters.’[iv]

The seemingly more clinical and humane killing of the enemy from afar in his aircraft, then, added to a slightly more sanitised war experience for some German aviators in the First World War. Indeed, in a Berlin speech from 21 March 1939, Göring drew upon their forebearers’ achievements in the Great War: ‘you can do that too, my boys, when the fatherland calls you. There is still a chivalrous fight up there in the clouds, in the sun.’[v]

The Germans had wielded great pride at Die Fliegertruppen des Deutschen Kaiserreiches (the ‘Imperial German Flying Corps’) – later reshaped into the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte from October 1916. Their aircraft were originally limited to reconnaissance, communications, and artillery spotting roles due to their inability to carry heavy loads or armament.

During the course of the First World War, however, more pilots on both sides took up arms in the sky and modifications were made that allowed flurries of machine gun fire to rattle through the propeller - as well as bombs to be dropped over enemy territory - with unprecedentedly destructive capabilities. Yet, an honourable aura soon cloaked the German aviators, who were memorably immortalised in a Schaberschul cartoon as ‘the upper ten thousand.’[vi]

At the heart of this rising kinetic airpower were the Jagdstaffeln (‘Fighter Squadrons’), who gained particular notoriety for their deadliness. This was particularly seen during the ‘Fokker scourge’ of 1915-16, in which the introduction of new Fokker Eindecker monoplanes terrorised the French Aéronautique Militaire and the RFC. As Peter Fritzsche has outlined, ‘Jasta tactics made the [German] pilot a self-reliant fighter and turned the skies into a hunter’s paradise.’[vii]

Haller noted how ‘there were no lads and youths in Germany whose dreams did not vibrate with the rousing drone of the fighter aircraft.…and who would be surprised that the boldest young warriors now all wanted to put on the fighter pilot's helmet!’[viii] The names of the First World War fighter pilots, he added, were ‘spoken in Germany like the heroes’ names in the Nibelungenlied’[ix] – a 12th-century German epic poem that details the heroic endeavours of knights and warriors.

The observed practice from both sides of dropping wreaths behind the enemy lines to commemorate a fallen opponent, too, epitomised the chivalric ‘knights of the sky’ narrative for both British and German aviators. As would later be seen with the Battle of Britain, however, it did also suit the RAF fighter pilots to particularly valorise their opponents.

McCudden claimed, for instance, that ‘it is foolish to disparage the powers of the German aviator, for doing so must necessarily belittle the efforts of our own brave boys, whose duty it is to fight them.’[x] He wrote of how ‘the skill and bravery of German pilots give me cause to acknowledge that the German aviators as a whole are worthy of the very best which the Allies can find to combat them.’

Similarly, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding - who commanded the RAF’s immortal Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain - would later claim upon the second anniversary of ‘Battle of Britain Day’ on 15 September 1942 that ‘the Germans were ‘worthy foes’ and how ‘That fact adds to the glory of our fellows beating them. The Germans had to take a terrific gruelling [pounding], and they stuck it for a long time, and I know of several acts of chivalry on their part.’[xi]

Consequently, when tracing how British and German aviators would later clash in the Second World War, it is important to flag up the early motif of each side praising the other as a ‘worthy’ foe – not just out of genuine mutual admiration, but also to justify the sacrifices and losses they had incurred when fighting one another. McCudden’s account of the Germans, however, was seen as being unusually positive for the time.

As The Aeroplane editor C. G. Grey noted in his foreword to McCudden’s memoirs, the latter had said ‘that he was sure he would be considered a pro-German when people read his views on the German fighting pilots.’[xii] This, as Grey outlined, demonstrated ‘a keen estimate of the mental processes of a certain type of English man and woman — the type which considers it treason to admire the high military qualities of the enemy.’[xiii]

Despite the early Zeppelin and Gotha raids of the First World War, then, the young men of the Luftstreitkräfte and the Royal Flying Corps had wrapped their war in the romance of knightly combat against their ‘worthy foes’. Yet this chivalric vision of the skies, forged in the Great War, would not fully endure under the unprecedented tragedies of Total War. The struggle for the skies in the Second World War would no longer be a tournament of knights; it would become a gladiatorial tussle.

References

[i] R. Stark, Wings of War: an airman’s diary of the last year of World War I. Translated from German by Claud W. Sykes. (London: The Military Book Society, 1973), 54-5.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] J. McCudden, Flying Fury: Five Years in the Royal Flying Corps [Kindle Edition] (Feldspar Press, 2017), 244.

[iv] H. Haller, Der Flieger von Rottenburg: Hanns Haller erzählt das Leben des Schlossergesellen und Kriegsfliegers Max Ritter von Müller (Bayreuth: Bayerische Ostmark, 1939), 66. Bibliothek des Deutschen Museums, Munich.

[v] Do 56/496. H. Göring, ‚Tag der Luftwaffe‘ Speech, 1 March 1939, in ‚Großdeutsche Luftmacht‘, Der Zeitspiegel, Series 8, No. 10. 9 March 1939. (Leipzig: MfDG), 11; H. Göring, ‘Tagesbefehl des Oberbefehlshabers der Luftwaffe‘, 21 March 1939, Berlin, in ‘Erlaß des Führers‘, Deutsche Luftwacht, 89 – 132.

[vi] P. Fritzsche, A Nation of Fliers. German Aviation and the Popular Imagination (Cambridge, Mass; London: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 85.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Haller, Der Flieger von Rottenburg, 66.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] McCudden, Flying Fury, 244; J. Sweetman, Cavalry of the Clouds: Air War Over Europe, 1914 – 1918 (Cheltenham: The History Press, 2011), 40.

[xi] ‘It Was Two Years Ago – Do You Remember? 185 German Raiders Crashed In a Day – “Divine Intervention”’, Bradford Observer, Tuesday 15 September 1942.

[xii] C. G. Grey, ‘Foreword’ in J. McCudden, Flying Fury: Five Years in the Royal Flying Corps [Kindle Edition] (Feldspar Press, 2017), 9 – 12.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Haller, Der Flieger von Rottenburg, 66.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] McCudden, Flying Fury, 244.

[xvii] C. G. Grey, ‘Foreword’ in J. McCudden, Flying Fury: Five Years in the Royal Flying Corps [Kindle Edition] (Feldspar Press, 2017), 9 – 12.

[xviii] Ibid.

When I was much younger (14, 15) I read a few books about FWW aerial combat and I recall reading about this “chivalry”. I remember thinking it wasn’t very chivalrous to blast vulnerable aircraft such as the B.E. 2 from the sky. I remember thinking that RFC aircraft looked particularly vulnerable, I’ve never forgotten it.

I noted this many times in conversations with US aces at AFAA conventions. In 1984, Galland, Rall and Krupinski were in attendance and having grand old times with Jim Goodson and Hub Zemke and others. Jim told me directly when I asked that "Most of us felt more affinity for the guys on the other side we were fighting, than for the other people on our side - we understood each other."

Another thing I noted was that if you didn't know who Gunther Rall was, you wouldn't have thought of him as a recently-retired head of the Bundesluftwaffe; he was another "hale fellow well met" at the bar. In my experience of all the interviews I have done, US flag officers still retain their "generalness" whatever clothes they're wearing. Same with Walter Krupinski. (Galland of course was Galland - one of a kind.)